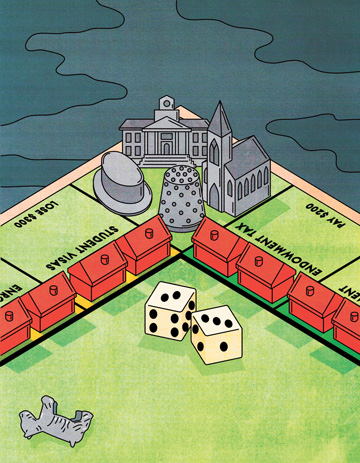

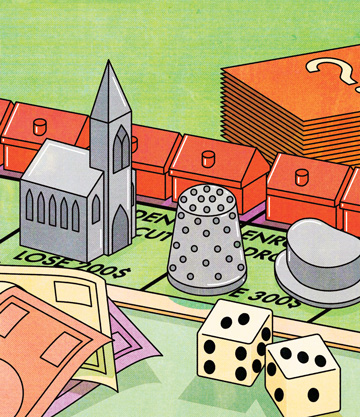

In the past year, turmoil has swirled around higher education in the United States as the current administration announced its intent to shut down the federal Education Department and issued a series of executive orders upending education policy. This summer, Congress passed the “One Big Beautiful Bill Act” that will make changes to higher education in other ways, including a new tax on endowments, limits on graduate loans, and changes to federal student loans. As well, Education Secretary Linda McMahon delivered a speech in September at Hillsdale College in Michigan in which she said, “The crisis of Higher Education is first and foremost a crisis of leadership.” She presented four “recommendations” for school leaders: prioritize students’ personal growth, seek and serve the truth, preserve and defend civilization, and model intellectual leadership and produce future thinkers and leaders. Some observers have described the four recommendations as pushback to the four academic freedoms from the 1957 U.S. Supreme Court case Sweezy v. New Hampshire, which has long defined higher education’s work, and they see this as pressure on schools to change. The In Trust Center’s Good Governance podcast brought Peter Lake, a Harvard-trained law professor and expert on higher education policy, together with the Rev. Dr. David Rowe, a former president and a current consultant, to discuss how schools can approach the changes. In this edited version of the podcast, here are four things theological school leaders should consider.

Curriculum

Lake: I think every president in this sector should read Linda McMahon’s speech because essentially the message is that the Hillsdale model is the blueprint. I think the thing we need to be focusing on is that there’s obviously a curriculum objective now. McMahon really emphasized this civilization point that’s embedded in her speech – teaching American civilization, even with an emphasis on the history of the West. I think the theological sector has become comfortable with the fact that there are a wide range of history and religion connections with curriculum and that has been really supported by the legal system. We’re going to have to see what is the meaning of what McMahon has articulated. Will there be sort of a preferred central narrative of American history and the role of religion in that history, and how will that fit with the various missions and articulations and teaching of different colleges that are out there? The speech was sufficiently ambiguous to leave open a multiple set of possibilities

If some of the schools that were subsidizing tuition with large endowments get taxed now in ways that they hadn’t been taxed before, that changes the calculations on that end.

Money issues

Rowe: There are some novel sources of revenue that are now under strain that they didn’t experience five years ago. If the amount that students can take out is limited in the Grad PLUS loan, then that really puts a constraint on what you can expect from tuition. We were already feeling rather constrained by what we were getting from tuition. If some of the schools that were subsidizing tuition with large endowments get taxed now in ways that they hadn’t been taxed before, that changes the calculations on that end. If there’s a test for earning potential on the other side of this, we have a long runway to be able to show that the M.Div. or other seminary degrees actually do meet some kind of objective criteria about that. I don’t think that these are different conversations than we’ve been having, but I think we might need to start speeding up the pace with which we’re actually addressing some of the fundamental characteristics of the business model that supports our mission. Because we have to think: How do we do this more effectively? How do we do this more efficiently? And I think there’s a long-term question for the church and in theological education in general: Why is it that there’s no earning potential in our degrees? Why can’t churches pay what it takes to educate somebody to lead the churches?

A new narrative

Lake: In her speech, McMahon articulates four academic responsibilities because of the Sweezy case, which we’ve relied on for years for the four academic freedoms of institutions. Instead of articulating four academic freedoms, this speech switches the narrative. What McMahon basically just said is the mission of the Education Department is not to protect historical academic freedoms of institutions, but to insist on the responsibilities that come with federal funding.

The Sweezy academic freedoms of another generation are very much trending now toward students. I think there’s been a shift in the freedoms in the academy thinking toward the rights and freedoms of students as opposed to institutions or faculty members. There’s been a seismic shift in the point of emphasis.

As tuition becomes very precious to the existential state of an institution, making sure the customers are satisfied becomes a major objective. Making sure the customers are happy and satisfied is a big part of the job, and that cuts into being controversial or challenging or even expressing one’s views in a way that one might think might generate controversy in some way.

As tuition becomes very precious to the existential state of an institution, making sure the customers are satisfied becomes a major objective.

Clarify convictions

Rowe: What do we have other than our theological convictions here in the theological education world and our beliefs? It’s been difficult for people to distinguish theological beliefs and civic beliefs, and to the extent that you’re using civic language to express theological conviction, this is a time where I think you might want to go and recover the theological language and the theological roots of that language. Be sure that you’re basing what you’re doing not in kind of a cultural hegemony around this idea, but you’re actually drawing on the biblical roots or the traditional roots of your faith and expressing that and living that out. Whether you’re on the conservative side of the spectrum or the progressive side of the spectrum, you can own that. I think we have to make sure that we’re really clear that what we’re doing is faith-based in theological education and in the highest traditions of the academy.

Lake: The strongest hand during this time is to get back to your roots and understand your traditions. If we aren’t saying it and living it in our everyday activities, then it potentially becomes more of a civic discussion. Get to your roots, get to your authenticity.

Listen to the full podcast episode: click here