It’s no secret that many theological schools are facing serious financial challenges. But most of these challenges start small. Enrollment is down by just a dozen students over the previous year. The markets perform just a percentage point worse than anticipated. Insurance rates for employees rise by a bit more than expected. Unexpected weather brings larger-than-normal maintenance costs.

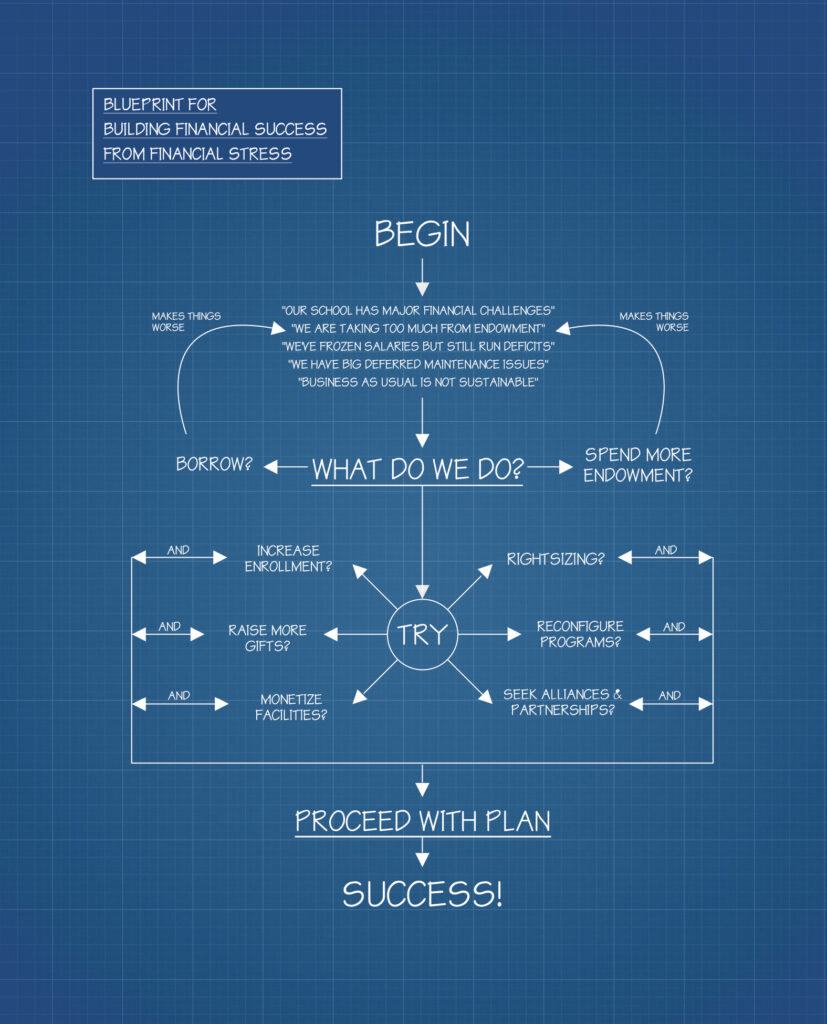

Unanticipated financial setbacks sometimes become little deficits. And the response to little deficits can shape the course of a school’s future. What are the options?

When expenses exceed income, that’s the very definition of financial stress. And when a theological school is stressed financially, the first response is usually to look for ways to enhance revenue. Enrolling more students, for example, increases tuition revenue, so sometimes the board and administration will urge the recruitment office to find more students. Many schools have added degree programs, such as specialized M.A. degrees or a D.Min. degree, to attract a broader student body.

But stepping up recruitment efforts can cost money — new brochures and mailings, new events, additional scholarship funds, sometimes even new staff. And adding a new academic program can, of course, incur very high startup costs. Yet even with efforts in this area, the needed uptick in enrollment may never materialize. Most seminaries have already been doing all they can to attract students. And even if enrollment does grow, the net increase in tuition may end up being merely incremental.

Some schools also look to development, saying, “We’ll just have to raise more money!” Yet successful fundraising usually occurs when there has been a vigorous program of identifying, cultivating, involving, soliciting, and thanking major donors. If these activities have atrophied over time, a reduction of gift income may have contributed to the school’s growing financial challenge.

Bouncing back can be challenging: It takes time to cultivate donors, and major givers are not usually inclined to support the elimination of deficits. In fact, the presence of significant deficits undermines the confidence that donors may have in the school, its management, and its board.

If new students and donors don’t erase deficits, it’s sometimes possible to look to facilities for relief. Some seminaries enjoy large campuses that can be monetized in various ways. For example, offices can be leased to other organizations, or whole buildings can be rented to other institutions. Many schools have found ways to partner with developers, turning their dorms into hotel rooms and their great halls into rentable event space. In more extreme cases, parcels on the edge of campus can be sold to adjacent property owners, or the whole campus can be sold so that the school can move into more cost-effective real estate — perhaps to rental space in an up-and-coming urban neighborhood, or to a large church with ample parking and easy highway access.

If a school has tried to increase enrollment and has already found ways to monetize their facilities, they might focus on cutting expenses. One way of doing that is to consider downsizing, or “right-sizing,” as it’s sometimes called. A zealous CFO can always find lines in the budget that can be trimmed, but one of the most effective ways to cut expenses is to reduce payroll — especially since personnel often accounts for 60 percent or more of a school’s expenses. Yet in a seminary environment, cutting staff is a hard sell and runs the risk of undermining the loyalty and morale of the employees who are left. Nonetheless, remaining staff and faculty may be happy to pick up the slack if they understand that the school has regained a firm financial footing.

Yet another way to eliminate a deficit is to adapt or eliminate one or more existing academic programs. Programs like music and counseling can be expensive, requiring unique facilities, specialized faculty, or additional accreditation. Weighing expenses and income, sometimes a school may decide to home in on the core mission and cut lower-priority programs that require a subsidy.

This is tricky territory, though. Sometimes a program that is on the fringe of the seminary’s core mission is actually breaking even or turning a profit. Sometimes — in fact, often — the program that serves as the core mission (like the M.Div.) is a money loser. Also, academic programs have constituencies — alumni, church leaders, and sometimes even foundations and donors. When eliminating a program, it’s always important to communicate that the core mission will go on, even if it’s in a new shape, form, or place.

Another way forward for a school facing serious financial difficulties is to think of entering into one or more partnerships. Partnerships can take many forms — from the sharing of library resources, to joint degree programs, to full institutional mergers or consolidations.

In recent years, one of the most popular forms of partnership in theological education has been the absorption of a seminary into a university of the same denomination, with the seminary becoming a graduate division of the larger school. Yet all forms of partnership can be tricky. In the first years of a partnership, cost sharing, policies, responsibilities, and administrative procedures have to be worked out. There may be clashes over relatively minor things, such as who has the right to use a classroom. Sometimes the promised cost savings are less than predicted. Major issues, such as the future fate of the theological school’s campus, endowment, board, faculty, staff, and programs, must be meticulously worked out beforehand.

Finally, there are two things that appear to be solutions for schools facing financial challenges, but are instead false friends: borrowing and drawing down the endowment. To be sure, borrowing can be a stopgap measure, allowing a school to buy time while growth strategies or transformation plans mature and show fruit. For example, in order to increase enrollment, a seminary may need to hire more staff or invest in more aggressive marketing.

Yet the risk is settling into the malaise of denial. No leader wants to be in charge when it becomes clear that a school can no longer fulfill its mission. Presidents and boards are perennially tempted to kick the can down the road, leaving it to the next leadership team to deal with. If they resort to borrowing, financial problems are exacerbated, and it grows harder for the school to transition to something new — or even to close the doors with dignity.

Another stopgap measure that often proves unhelpful in the long run is drawing down the endowment. A safe approach is to keep the annual draw below 5 percent (based on a 12-quarter rolling average) — or, better yet, below 4.5 percent. But some schools draw 7 percent, 8 percent, or even 9 percent annually. At that rate, an endowment shrinks rapidly. Unless there is a realistic plan to restore financial health, schools that do this dig themselves a deep financial hole and increase the severity of whatever challenges they are already facing.

The solutions that I’ve enumerated here are not necessarily undertaken in order. Some schools start with borrowing — and then realize they need to make cuts. Sometimes a prized academic program is initially saved from the chopping block, but later, after other strategies have been tried, it becomes evident that the beloved program must be eliminated after all. The board can exercise considerable courage in facing the financial stress — by insisting on careful and thorough financial analysis and an equally thoughtful consideration of alternatives. Their fiduciary duty always requires them to find a sustainable way to fulfill the mission.

The most important advice for schools facing financial stress? Open your eyes and be realistic. If you’re starting from a position of financial stress, figure out what your situation is and discuss realistic possibilities for turning around. Closing your eyes to financial realities is the worst gift you can give to your students, your alumni, your faculty and staff, and the church.