Money is a fraught subject for many religious and educational leaders, but for the sake of religious institutions, for the sake of the spiritual and moral lives of those entrusted to their care, the anxious silence surrounding the subject of money ought not continue.

Many of the religious leaders we recently interviewed said their seminary education did not provide adequate, or any, theological or leadership training on money and its management, and most said they wished it had been otherwise.

For example, consider the case of an evangelical pastor who told us he felt overwhelmed when he moved from a small rural congregation in the South to his current, much larger Midwestern congregation of 400 — a church that also operates a school with more than 500 students. He went from overseeing an annual budget of $150,000 to overseeing an annual budget of $3 million and a staff of 100. Seminary did not prepare him for such a challenge.

Some of the anxiety religious leaders feel about money may stem from a lack of training on the specifics of financial management. Another factor may be a lack of knowledge about stewardship and fundraising. Or it may be a need to situate their own congregations in context, comparing themselves to others of similar size, location, age, or religious tradition. Whatever the reason, there are many resources for religious leaders to draw upon, to help them navigate what is decidedly an important part of their role. Without the necessary resources, it can be hard for religious leaders to know where to start.

In this article, we would like to share some of our insights, as well as those of our colleagues, on the data we gathered while working as researchers on the National Study of Congregations’ Economic Practices (NSCEP) project. This will shed a bright light on how congregations receive, manage, and spend their money.

The first insight

The first general insight is that the data complicates the popular narrative that religion is in decline.

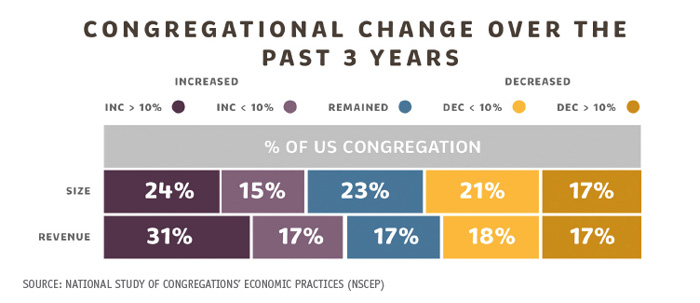

While general surveys, including those by Pew and Gallup, report declines in religious affiliation and church attendance, these trends do not automatically signal what is happening at the congregational level. Our research shows that 39 percent of congregations reported an increase in attendance, 38 percent reported a decrease, and 23 percent saw no change.

Congregations that are declining in attendance do not necessarily report a decline in revenue. In fact, overall financial data were more positive than attendance data: 48 percent of congregations reported an increase in revenue, 35 percent reported a decrease, and 17 percent reported that revenue remained the same.

How is that possible? It may be that fewer people are shouldering a greater share of the congregation’s donations. Or it may be that congregations are finding alternative streams of revenue, such as renting out their facility (for example, for weddings or conferences) or operating auxiliary enterprises (such as schools or day care centers). Some congregations have seen revenue from bequests, gifts and from endowments.

Significance: While only 24 percent of congregations experienced membership growth of more than 10 percent in the previous three years, 31 percent of congregations experienced revenue growth of more than 10 percent. The news about congregational finances is not all bad.

But there may be a simpler explanation, says Brad Fulton, codirector of the NSCEP, and a faculty member at Indiana University: “If the old maxim that 20 percent of a congregation’s participants give 80 percent of donations remains true . . . the people who are really committed tend to give a lot more.”

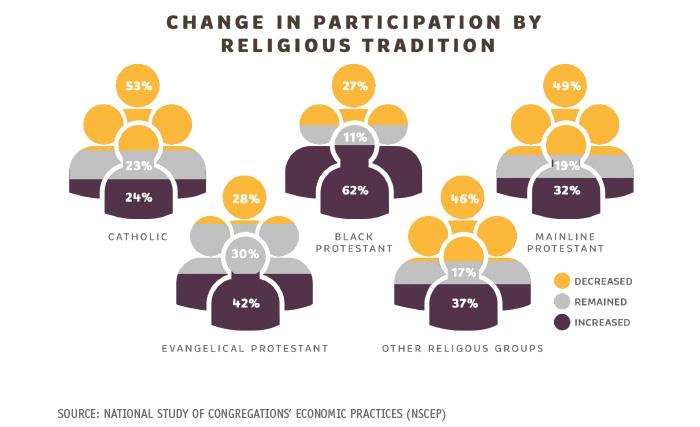

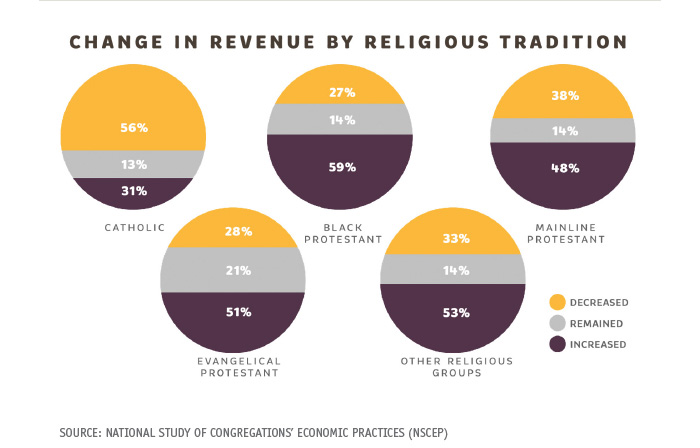

Different faith traditions report different experiences with finances. Catholic congregations face the greatest challenges, with more than half of all parishes declining in both revenue and size over the past three years. On the other hand, while half of mainline Protestant congregations reported a decline in size, only 38 percent reported a decline in revenue. Of black Protestant congregations, 51 percent reported growth in both size and revenue. Of all faith traditions surveyed, evangelical congregations most often reported no change in size or revenue.

Significance: Change in religious participation may be compared across religious traditions. For example, while only 24 percent of Catholic parishes experienced higher levels of participation in the previous three years, 62 percent of black Protestant congregations experienced higher levels of participation.

Yet while many religious congregations are seeking innovative sources of funding, research shows that 81 percent of congregational income continues to come in the old-fashioned way: from direct individual contributions. Of those individual contributions, 78 percent are given during weekly worship services. Thus, the regular weekly offering — a face-to-face invitation to support the congregation’s mission — continues to be a strong source of revenue for churches.

While 92 percent of congregations reported passing the plate each week, only 46 percent offer a digital giving option and of regularly participating adults, only 24 percent made at least one digital contribution to their congregation in the last year.

Significance: Change in congregational revenue may also be compared across religious traditions. For example, while 31 percent of Catholic parishes experienced increased revenue in the previous three years, 59 percent of black Protestant congregations experienced increased revenue.

These findings lead to the question: Are congregations modifying their practices to meet the changing needs of their communities? And from that follows another question: Are churchgoers being given instruction about why giving is important and what the best way is to give? A mere 9 percent of congregations reported that the congregation received weekly instruction on giving — yet the overwhelming majority of this 9 percent reported that they experienced revenue growth.

This hints at a missed opportunity for the other 91 percent. If these congregations were to offer instruction on giving through sermons, testimonies, prayers, and religious education, not only might they see increased revenue, but it is possible that in the future, money might be considered a less taboo subject than it now is.

Asking, teaching, and stewarding

Because now, more than ever, religious congregations compete with other nonprofit organizations for charitable dollars, religious leaders need to make the case for why congregations are good stewards of charitable giving.

One step in that direction is to get over the hesitation to talk about money. For example, while all leaders of nonprofit organizations know who their major contributors are, only 55 percent of congregations reported that the head clergyperson had access to donors’ giving records. And of this group, only 58 percent said they had actually looked at the records. The most common reason for not looking was to avoid giving preferential treatment to certain donors.

Of the congregations in which clergy said they did look at the donation records, 58 percent reported an increase in revenue over the three-year period of the study — with 42 percent citing an increase of 10 percent or more.

In fact, one leader — a church planter in his early 40s from the northeastern United States — said that one of his mentors had challenged him to reach out to top donors. The mentor asked, “Why don’t you just connect with them and thank them for what they’re doing and how they’re giving to our church?” He added that clarity around giving was the key to strong relationships with parishioners.

When religious leaders talk about money and the issues surrounding it, it is important to talk about more than the logistics of giving. Instead, they should facilitate broader conversations about the meaning of money — how it makes people feel, their experiences with it, and obstacles to giving. Almost one-third of congregations reported they already had established groups or classes on personal finance. These gatherings are a prime opportunity to explore principled economic strategies, including charitable giving. Engaging in broad conversations about money can help institutions and individuals align their faith and values with their economic decisions, and this may refocus any squeamishness they may feel about money. For people of faith, decisions of how to spend money can never be separated from who they are as followers of a generous God.

Spending

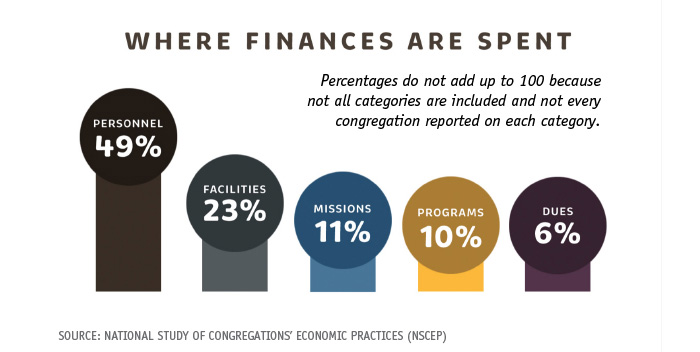

Congregations spend nearly half of their revenues on paying clergy and staff, and another 23 percent on facilities, which includes maintenance and mortgage. About 10 percent of revenues are spent on programs, 6 percent on dues, and about 11 percent on missions, outreach, and other programs outside of the walls of the building, whether locally, nationally or internationally.

Congregations are often criticized for spending the bulk of their budgets on themselves, yet many see personnel as essential to the fulfillment of their missions.

Significance: A large majority of congregational revenue comes from individual donations.

Brad Fulton, codirector of the NSCEP, says that most congregations support causes outside their own walls, both in their own communities and around the world: “Eighty-four percent of congregations have participated in some type of social service or community development program in the last year, from offering food and clothing to addressing physical or mental health needs or providing disaster relief.” That’s a significant investment of roughly $10.6 billion annually on missions, service and charity.

Significance: Like most nonprofit organizations, religious congregations spend a significant portion of their revenues on personnel.

Learning about money and mission

The top topics seminary graduates most often say they are unprepared for are financial management and fundraising — and these are precisely the topics clergy say are most central to their work. Clergy not only instruct congregants (who, like most Americans, struggle with consumerism and debt) on the proper use of resources, but they also raise funds for the annual budget, capital expenses, and emergencies.

As religious affiliation and church attendance patterns change, how can theological schools equip religious leaders with the tools they need to address economic issues? The future of the church and our religious lives may depend on it.

A national study

The National Study of Congregations’ Economic Practices (NSCEP) is a large, comprehensive research project on how congregations receive, manage and spend their money. Based on surveys of more than 1,200 congregations from almost every religious tradition, it was conducted in 2018 by researchers from the Lake Institute of Faith and Giving at the Indiana University Lilly Family School of Philanthropy, with the help of NORC (formerly the National Opinion Research Center) at the University of Chicago. This article was written by two members of the study’s research team. More information on the study, including executive reports, can be found at www.nscep.org.

The researchers continue to explore the data and to conduct interviews with pastors.

Four steps to better congregational finances

- Do your homework. Understand how your congregation receives financial support. Who are your givers? Why do they give? How do they give? When do they give?

- Talk about money. Do not shy away from talking openly about finances. Bring in special speakers and offer classes on personal finance, estate planning, and charitable giving, for example.

- Frame finances through mission. Reinforce the idea that personal and congregational finances are connected, and together they support the congregation’s mission in the community and the world.

- Assess your technology. Is your congregation making it easy for people to give, including on their phones?