It’s not secret. North American theological schools are facing major challenges in the early years of the 21st century. The recession of 2008 hit seminaries and divinity schools hard, but even before the financial downturn, they were facing declining enrollment and soaring overhead.

It’s not secret. North American theological schools are facing major challenges in the early years of the 21st century. The recession of 2008 hit seminaries and divinity schools hard, but even before the financial downturn, they were facing declining enrollment and soaring overhead.

A shrinking population is the most corrosive problem a school can face. It inflicts financial damage on campuses that rely primarily on tuition payments, and even schools with generous endowments find that undersubscribed courses dampen the morale of faculty, staff, and students. Most troubling, a dearth of students raises fundamental questions: Is the mission of the school still relevant? Is it needed in its present form?

In the forums where the leaders of theological schools meet, there is candid conversation about enrollment problems: lower student headcounts and decreasing full-time–equivalent (FTE) enrollment numbers, especially in longer programs like the master of divinity. At the same time, presidents and deans report some good news: Their schools are attracting excellent students, including, in some schools, a growing number of recent college graduates—a cohort that had diminished sharply since the mid-20th century. These encouraging trends suggest the future is not as bleak as straightline enrollment trends may suggest.

The Auburn Center for the Study of Theological Education designed its current study, Pathways to Seminary, as a follow-up to its 2001 report, Is There a Problem? Theological Students and Religious Leadership for the Future (which is available online at auburnseminary.org/report/is-there-a-problem/). The research team wanted to explore the complexity of declining enrollments and the continuing presence of very good students. This article reports key findings about enrollment trends. In a future issue of In Trust, another article will explore students’ path to seminary and summarize how their vocational aspirations took shape before and during their seminary years.

Enrollment: What happened?

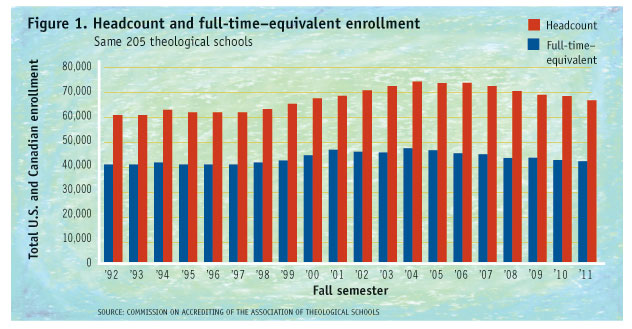

Figure 1 shows that the story of seminary enrollments is complicated, but we can sum up its overarching pattern simply: growth and decline. Over the past two decades, enrollments in graduate-level North American theological schools peaked in 2004, and then began to decline at about the same rate that they had grown. Net gains were small. By the end of the 20-year period, headcount enrollment gained on average 0.5 percent a year. Enrollment measured on a full-time–equivalent basis gained less than 0.2 percent per year on average. By contrast, according to the National Center for Education Statistics, master’s level programs in U.S. higher education—the category that includes most seminary degrees—increased at more than 10 times that rate.

Figure 1 shows that the story of seminary enrollments is complicated, but we can sum up its overarching pattern simply: growth and decline. Over the past two decades, enrollments in graduate-level North American theological schools peaked in 2004, and then began to decline at about the same rate that they had grown. Net gains were small. By the end of the 20-year period, headcount enrollment gained on average 0.5 percent a year. Enrollment measured on a full-time–equivalent basis gained less than 0.2 percent per year on average. By contrast, according to the National Center for Education Statistics, master’s level programs in U.S. higher education—the category that includes most seminary degrees—increased at more than 10 times that rate.

What factors drove growth and then contributed to decline? No one knows for sure. Growth occurred when evangelical groups were expanding and becoming a majority presence within the theological school community. Today all religious groups, including evangelicals, are losing strength, and seminary enrollment patterns track this change rather closely. Broader social forces and trends may be in play as well, such as economic constriction and changing patterns of participation in higher education.

There are significant variations in the patterns of growth and decline. Factors such as degree program, the structure and religious family of the school, gender, age, and race may help us to understand the patterns in more detail.

Degree programs

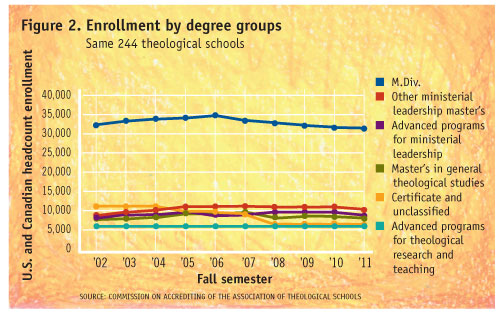

Figure 2 shows how patterns of growth and decline have varied across degree programs. The master of divinity degree has sustained major losses (7.5 percent of its enrollment since its peak in 2006). The master’s degree in general theological studies, not intended as ministerial preparation, has lost an even greater percentage (11 percent since 2005). No program type has gained during this period, although non-M.Div. ministerial master’s degrees have lost less (about 3 percent since their peak in 2008) and advanced ministerial degrees such as the D.Min. have held fairly steady. The steepest decline has been in the category of non-degree enrollments—labeled “certificate and unclassified” in Figure 2.

Figure 2 shows how patterns of growth and decline have varied across degree programs. The master of divinity degree has sustained major losses (7.5 percent of its enrollment since its peak in 2006). The master’s degree in general theological studies, not intended as ministerial preparation, has lost an even greater percentage (11 percent since 2005). No program type has gained during this period, although non-M.Div. ministerial master’s degrees have lost less (about 3 percent since their peak in 2008) and advanced ministerial degrees such as the D.Min. have held fairly steady. The steepest decline has been in the category of non-degree enrollments—labeled “certificate and unclassified” in Figure 2.

As a result of these changes, the master of divinity program is becoming less prominent. In 1992, 69 percent of students were enrolled in M.Div. programs; today that has diminished to 63 percent. Meanwhile, all the modest enrollment gain over two decades has been in “professional” M.A. degree programs intended to prepare for various ministries. These programs enrolled 14 percent of students two decades ago; now they enroll 20 percent.

Religious tradition and type of school

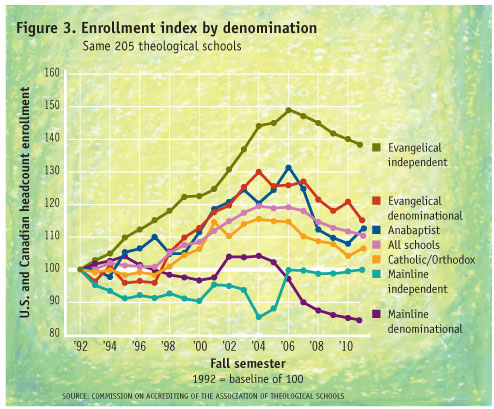

Gains and losses were spread unevenly across schools of different religious traditions, although almost all follow the same pattern. Figure 3 is an indexed graph that sets the 1992 total enrollment of all denominational traditions at a fictitious level of 100 to show different rates of growth over the 20-year period.

Gains and losses were spread unevenly across schools of different religious traditions, although almost all follow the same pattern. Figure 3 is an indexed graph that sets the 1992 total enrollment of all denominational traditions at a fictitious level of 100 to show different rates of growth over the 20-year period.

-

The enrollments of evangelical independent schools (schools with no denominational ties) grew very fast before 2006 but then began to decline.

-

Evangelical denominational schools and Roman Catholic schools also grew, although the growth started later and peaked sooner.

-

Mainline denominational schools grew slowly and then sustained heavy losses. • Anabaptist schools, whose enrollment is small, grew fast by adding a few students.

-

Mainline independent schools did poorly at the beginning of the period but rebounded to a plateau at the end.

Independent schools stand out in this analysis — the evangelical ones because of their fast growth and mainline Protestant ones because they counter the recent pattern of decline. Nondenominational schools draw students from a larger pool. The lack of a denominational constituency may give them the incentive to recruit aggressively. Some evangelical independent schools have the added advantage of large size, and several have led the way in creating distance learning programs and satellite campuses, which bring additional students. The convenience of these programs and locations may attract students who otherwise might travel to attend their denominational seminary. The category of independent mainline Protestant schools includes some that serve racial/ethnic constituencies. The enrollment of some of those groups is increasing even as the enrollment of whites declines.

Gender

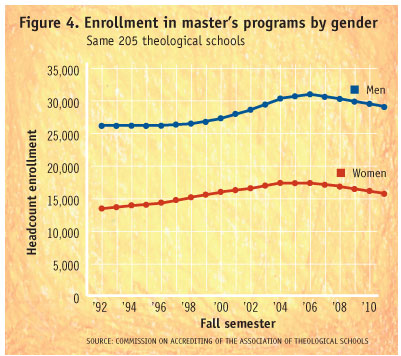

As Figure 4 indicates, male and female enrollments show growth and then decline, but at different rates. In 2011 there were 40 percent more women in North American theological schools than 20 years earlier; meanwhile, enrollment of men increased only 12 percent. Once enrollments began to dip, female enrollment fell faster. In the six years since male enrollment peaked, the loss was 1 percent a year, but women lost 1.5 percent a year over a seven-year period. The rapid growth no doubt incorporated the influx of women, especially older women, who came to seminary after mainline denominations began to ordain them in significant numbers and, later, when Roman Catholic and evangelical churches and agencies opened a range of ministries to women. The sharp subsequent decline may have occurred because the backlog was used up. Because of women’s earlier gains, the proportion of women to men has remained fairly stable. In 1992 women were 32 percent of master’s-level enrollments. Less than a decade later, in 1999, they were 37 percent, and they have remained at that level ever since.

As Figure 4 indicates, male and female enrollments show growth and then decline, but at different rates. In 2011 there were 40 percent more women in North American theological schools than 20 years earlier; meanwhile, enrollment of men increased only 12 percent. Once enrollments began to dip, female enrollment fell faster. In the six years since male enrollment peaked, the loss was 1 percent a year, but women lost 1.5 percent a year over a seven-year period. The rapid growth no doubt incorporated the influx of women, especially older women, who came to seminary after mainline denominations began to ordain them in significant numbers and, later, when Roman Catholic and evangelical churches and agencies opened a range of ministries to women. The sharp subsequent decline may have occurred because the backlog was used up. Because of women’s earlier gains, the proportion of women to men has remained fairly stable. In 1992 women were 32 percent of master’s-level enrollments. Less than a decade later, in 1999, they were 37 percent, and they have remained at that level ever since.

Race

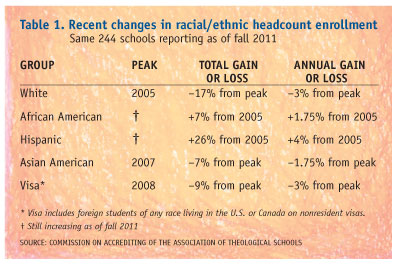

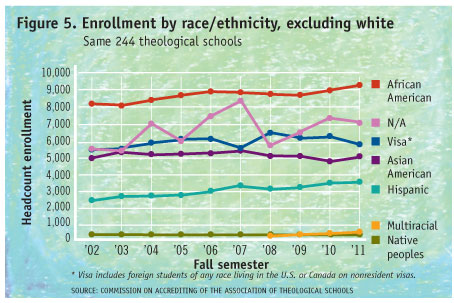

The most striking variation in the general “growth followed by decline” enrollment pattern is visible when nonwhite racial and ethnic groups are separated out from white students. Figure 5 and Table 1 illustrate the enrollment trends.

The most striking variation in the general “growth followed by decline” enrollment pattern is visible when nonwhite racial and ethnic groups are separated out from white students. Figure 5 and Table 1 illustrate the enrollment trends.

While white enrollments have lost 17 percent since peaking in 2005, African American and Hispanic enrollments have grown. The Hispanic group, small to begin with, expanded dramatically. Asian American enrollments apparently fell, but the decline began later and has been slower. Enrollments of “visa” students (foreign students of any race on nonresident visas) peaked later, in 2008.

Age

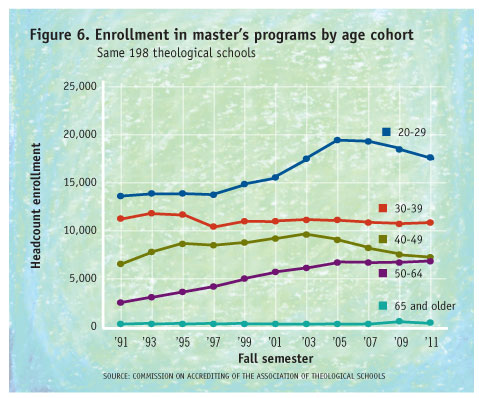

Ten years ago, age was the most discussed feature of student enrollment. The average age of a student entering a master’s-level program was about 35, and the cohort of students between 30 and 49 was growing fast (31 percent in the 1990s). (For more on this, see auburnseminary.org/report/is-there-a-problem/, page 5.) But as Figure 6 shows, the growth of the 30–39 and 40–49 master’s cohorts peaked in 2003. Meanwhile, the 20–29 age group saw steep growth between 1997 and 2005, followed by a decline. The 50–64 age cohort, once small, grew fast and continuously. These two developments—growth in the youngest and oldest cohorts—are the prominent features of the age profile of students today, though the recent decline in the youngest cohort may signal another change in years to come.

Ten years ago, age was the most discussed feature of student enrollment. The average age of a student entering a master’s-level program was about 35, and the cohort of students between 30 and 49 was growing fast (31 percent in the 1990s). (For more on this, see auburnseminary.org/report/is-there-a-problem/, page 5.) But as Figure 6 shows, the growth of the 30–39 and 40–49 master’s cohorts peaked in 2003. Meanwhile, the 20–29 age group saw steep growth between 1997 and 2005, followed by a decline. The 50–64 age cohort, once small, grew fast and continuously. These two developments—growth in the youngest and oldest cohorts—are the prominent features of the age profile of students today, though the recent decline in the youngest cohort may signal another change in years to come.

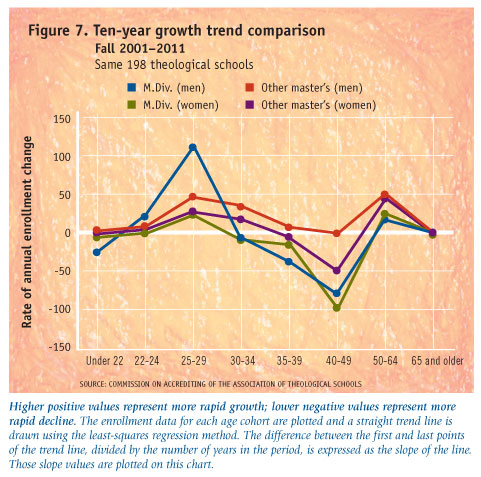

These developments are dramatized in Figure 7. Over the most recent decade, the enrollment of men and women in the M.Div. and other master’s programs has increased substantially in the 20s and 50s cohort and fallen for the 35–49 cohorts of students.

These developments are dramatized in Figure 7. Over the most recent decade, the enrollment of men and women in the M.Div. and other master’s programs has increased substantially in the 20s and 50s cohort and fallen for the 35–49 cohorts of students.

Program formats

In recent years, many schools have opened extension sites for students who cannot travel to the main campus. Creating and maintaining such sites requires resources, and perhaps for that reason, large schools have the most extension students. Slightly more than half of the schools with the largest extension enrollments had better enrollment trends—either more growth or less decline— than schools at the mid-point in a ranking by growth/decline. Since 2007, enrollment at extension sites has begun to decline, mirroring overall enrollment decline.

Many schools are planning or implementing distance-education programs, usually in the form of online courses, to bolster enrollments. Again, larger schools have the resources to launch and maintain such programs and report the largest distance-education enrollment. Online education in these schools is mildly associated with more growth or less decline. In smaller schools, there is no association between online offerings and a favorable enrollment picture. Enrollments in distance education have continued to grow, in contrast to the overall pattern of enrollment decline. At an earlier time some online students might have enrolled at extension centers. Many online courses are taken by students who are in residence on campus, so it is impossible to determine what proportion of online students enrolled only because the option was available.

Implications of growth and decline

Because most schools saw some growth in the 1990s, the stagnation of the early 2000s and the recent downturn in almost all sectors were probably surprising and unwelcome to them. In summary, here is what the data reveal:

-

Decline. Total headcount and FTE enrollments have declined in recent years. In the 205 schools for which 20-year data are available, the decline began in 2005. Collectively, all schools that are currently members of ATS show enrollment trending downward.

-

Fewer men. There are now fewer males in master’s level programs than 20 years ago, and losses of male students have accelerated in schools of all religious groups except Roman Catholics. Numbers of white male students also are declining fast.

-

Fewer M.Div. students. Losses in both master of divinity and general theological master’s degree enrollments began earlier and have been steeper than losses in other programs.

-

Fewer women. Accelerating even faster is the decline in numbers of female students, a group that gained considerably since 1992, and then began to shrink five years ago.

-

Fewer 30- and 40-somethings. The middle-age categories that provided the majority of masters’ students 20 years ago—students in their 30s and 40s—have been getting smaller.

We know that North Americans are increasingly less likely to identify with a religious group and less likely to participate regularly in organized religious activities. Diminishing student interest in theological education corresponds to those developments in various religious sectors.

Mainline Protestant decline began decades ago, and so did enrollment decline in its theological schools. Losses of what had been its traditional constituency, white male recent college graduates, have been enormous. In the 1980s and early 1990s, women took up some of the enrollment slack, but now their numbers are declining.

Evangelical Protestantism enjoyed a boom in the late 20th century, and the enrollments at schools associated with the movement also mushroomed. Sociologists now report that membership is declining in evangelical churches, and seminary enrollments are down. Total headcount enrollment is declining, and full-time-equivalent enrollments are declining even faster. Total course credit levels are falling as more students enroll in shorter M.A. programs and fewer in master of divinity programs. The losses are not great—they do not erode the gains of the prior period—but they are felt keenly, because most evangelical theological schools are tuition dependent.

Roman Catholicism presents a complex picture. “Membership,” as measured by those who self-identify as Catholic, continues to grow, but participation and many institutional features (numbers of schools, membership in religious orders, and numbers of clergy) have declined since the 1960s. Catholic theological schools felt the impact of these shifts well before the period covered by this study, and a number of institutions closed or merged as a result. In part because the Catholic seminary system now has less overcapacity, the impact of recent losses has been less severe.

Eastern Orthodoxy presents an even more complex picture, with much debate about membership statistics, and has too few seminaries to make generalizations possible.

The implications of these findings for theological schools are sobering. Few if any institutions can count on substantial enrollment growth in the next period. Powerful religious and social trends, including shrinking college enrollments now that the numbers of 18-year-olds has peaked, make an enrollment turnaround unlikely. Schools whose plans call for greatly expanded enrollments should revise those plans, or at least create alternative strategies in case their enrollment hopes are not realized.

At the same time, schools can act to sustain the enrollments they have and perhaps to increase quality as well.

For instance, enrollments of students in their 20s have increased at a faster rate than most other age cohorts. This may be due in part to changing values: there is evidence that recent graduates are more altruistic than they were 20 years ago. Theological schools have made efforts to recruit this cohort, and some have succeeded in attracting a critical mass of younger students. Their experience seems to be evidence that well-planned and well-executed recruitment may work. At the same time, the recent decline in this age category bears close attention.

The steady growth of the cohort of students 50 and older—evident in North American schools of all traditions and types—is less understood. It is unclear what impels these students toward seminary and ministry. It may be that changing cultural norms have made it respectable to retire fairly young from one occupation and begin another. Schools that discover what motivates their older students may be able to recruit more in the same category. Even if these are not the most desirable students, because of the short time they will serve, their presence can bolster enrollments.

In planning recruitment strategies, the experience of nondenominational schools may be instructive. These institutions have been less damaged by enrollment downturns. One obvious reason is that schools not restricted by denominational requirements draw from larger pools of potential students. Such schools do not, however, have a guaranteed constituency: they attract students only if their offerings are more appealing than those of their competitors. It is likely that they achieve their relative enrollment success by fitting their educational programs to the needs and interests of potential students. Augmented by well-organized recruitment efforts, this is a strategy all schools can adopt.

One demographic trend seems to draw new constituencies to theological education and holds promise to continue in the future. Nonwhite populations of North America are growing and so are the enrollments of African Americans and Hispanics in theological schools. Rising black enrollments probably reflect rising expectations for ministry in black churches and a larger pool of college graduates eligible for further study, while Hispanic enrollments are no doubt bolstered by immigration and educational advances. (Data show that between 1990 and 2010, the number of black students enrolled in U.S. undergraduate programs more than doubled and the number of Hispanics tripled.) Schools that make efforts to serve these groups are likely to see sustained and increased enrollment. Meanwhile, Asian enrollments have held fairly steady and may grow in the future.

Our research indicates that the efforts of denominations and ecumenical agencies to stimulate interest in seminary and ministry among teenagers and college students have contributed to the increase in younger student enrollments. The more a school is connected to programs that bring young people into its ambit, the more likely that school will have younger students in its future classes.

Here is some final good news: the measures that are good for a school’s enrollment picture—realistic institutional planning, incorporating new groups into old-line religious bodies, cultivating the young —are the measures that will help rebuild religion in North America. By identifying and recruiting the best students, theological schools serve the church in critical ways and empower it to serve the world.

About the study

The research team from the Auburn Center for the Study of Theological Education was led by Barbara Wheeler and included senior research fellow Anthony Ruger and associate director Sharon Miller. To explore trends in enrollment, the team analyzed data provided by the Commission on Accrediting of the Association of Theological Schools (ATS), which collects the information annually from member schools.

Of the association’s current membership of 271 schools, 205 reported consistently for the 20-year-period and were included in the longitudinal analysis. For the study of more recent trends, data from larger numbers of schools reporting consistently over shorter periods were available. To gain a deeper understanding of the students identified by their institutions as highly promising, the research team conducted more than 250 interviews at 24 schools, asking interviewees about their pathways toward seminary. For these interviews, the team was joined by Helen Blier of ATS and Melissa Wiginton of Austin Presbyterian Theological Seminary. Findings from these interviews will appear in a forthcoming publication from the Auburn Center for the Study of Theological Education.