Most Sundays, as we drive to church, the Hiemstra family passes runners decked out in spandex, racing through town in groups of 20 or 30. “They’re running to church,” I sometimes say to my kids. “They’re rushing to get good seats!”

They are old enough to know that I am joking. Running groups, like Sunday mornings at the hockey rink, are increasingly what passes for Canada at prayer. The church in Canada has received a lot of attention lately. For example, last year a story in Maclean’s magazine examined changing trends in who is going to church and who is not. Polls have probed church attendance, tying declining religious participation to changing demographics. Weekly attendance at religious services in Canada is just 13 percent, according to a December 2013 poll by the Evangelical Fellowship of Canada (EFC) and the Angus Reid Forum, a national polling firm. That 13 percent includes all faiths, not just Christians.

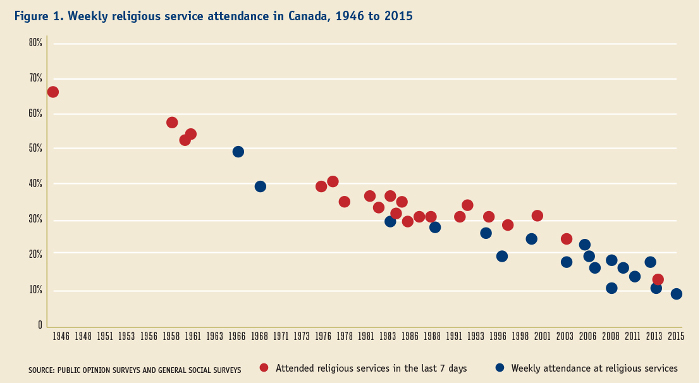

What does a number like this mean? Just after World War II, 67 percent of Canadians told Gallup that they had attended a religious service in the previous seven days. In those days, Gallup measured religious service attendance around Easter, but even with an allowance for seasonal piety, a much larger share of Canadians were churchgoers then. Even in the mid-1980s, about one-third of Canadians could still be found in a worship service at some point on any given week.

A steady fall

As Figure 1 shows, the fall in attendance has been steady since World War II, but between 2003 and 2013 religious activity ran into turbulence, and participation dropped to a lower plane. Twenty percent of Canadians told Ipsos-Reid they attended religious services weekly in 2007 — virtually unchanged since 2003. But by 2013, that number had dropped to 13 percent, and 2.5 million fewer Canadians were at public worship in any given week.

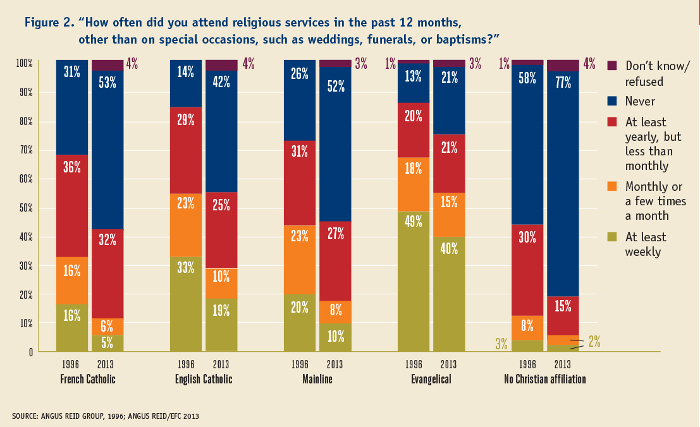

The declines have not been shared equally across religious traditions. As Figure 2 shows, the number of French Catholics who say they attend Mass weekly fell from 16 percent in 1996 to five percent in 2013. For English-speaking Catholics, the numbers dropped from 33 percent to 19 percent. For mainline Protestants, the numbers who attend church weekly dropped from 20 percent to 10 percent. And among evangelicals, the number fell from 49 percent to 40 percent.

Attendance vs. affiliation

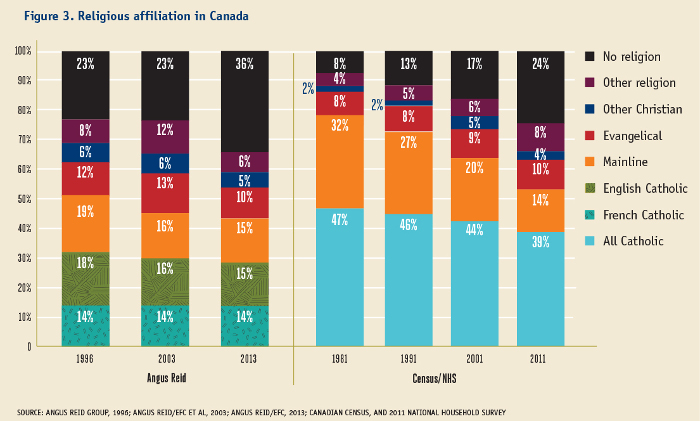

Attendance hasn’t been the only decline — affiliation has also seen sharp drops among some groups, especially mainline Protestants. (“Affiliation” counts people who say they belong to a church, irrespective of attendance.) For example, in 1981, 32 percent of Canadians said they were affiliated with one of the mainline Protestant churches (Anglican, Lutheran, Presbyterian, or United Church of Canada).

But 30 years later, in the 2011 National Household Survey (a general social survey that replaced the long-form census), just 14 percent of Canadians identified with one of these historic Protestant denominations — a drop of more than 50 percent. To state the data in another way, there were 7.7 million mainline Protestants in Canada in 1981, but in 2011, there were only 4.6 million mainline Protestants in a country that had grown by 8.7 million residents. The respondents who said they had “no religious affiliation” grew from eight percent to 24 percent.

Most of these “religious nones,” as they’re sometimes called, would have formerly identified as Christian. A 2011 study titled “Hemorrhaging Faith,” conducted by a partnership of Canadian organizations intent on understanding patterns of church attendance, found that when children reared in the church depart, or disaffiliate, the vast majority leave organized religion all together — they do not join other faiths.

This swelling of the ranks of the “religious nones” is even greater if we look at the answers Canadians give to pollsters instead of census takers. As Figure 3 shows, Canadians report themselves as more religious when speaking to government officials than they do when talking to pollster Angus Reid.

Canada’s graying church

Like most Western nations, Canada is aging, and demographers warn of the consequences of the retirement of the Baby Boom generation, born between 1946 and 1964. But some traditions are aging faster than others — for example, immigration is keeping the evangelical and Orthodox churches younger and more diverse than the mainline Protestants.

About 22 percent of Canadians are immigrants, and they tend to be younger than the national average, to have more children, and to be more devout. Asians and Africans, who are the newest immigrants, also tend to have the highest levels of religious affiliation and attendance. A 2013 Angus Reid study found that immigrants from Asia and Africa are in church more than twice as often as people born in Canada.

As Figure 4 shows, immigrants seem to be filling the pews of every tradition except the Protestant mainline. Among Orthodox Christians, 57 percent are immigrants, and 70 percent of those immigrants arrived after 1981—many from the Middle East. Catholic churches, too, have been bolstered by immigrants from places like the Philippines. Among all Canadian evangelicals, a quarter were born outside Canada, and three quarters of these immigrants arrived after 1981.

By contrast, only a tenth of mainline Protestant Christians are immigrants, and most of these are older, having arrived before 1981.

The sunny side

According to the 2015 Large Church Canadian Survey, 300,000 Canadians, or one in eight of all churchgoing Protestants, attend a “large” congregation — one with at least 1,000 in attendance each week.

The new report says that about 150 Canadian churches have more than 1,000 in attendance, and nearly 80 percent of them reported an increase in attendance over the last five years. Their growth comes from within the congregation (31 percent of respondents grew up in the congregation), from transfers (23 percent joined from other local congregations), and from relocation (17 percent moved from another city).

So even as we pass those runners dashing around town on Sundays and I make my tired joke, we know that there are still Canadians going to church. Congregations have suffered blows in their attendance, but they haven’t yet been defeated — they are down, but not out. As some churches dwindle, others grow, and as some age, others are revitalized by immigration and by young families who seem to be searching for big and better.

The next 20 years will be fascinating to watch.

An earlier version of this article was presented at the 2015 joint meeting of the Associated Church Press and Canadian Church Press.

Canadian demographic changes and theological education

All theological education in Canada is undergoing a crisis,” says David Guretzki, dean of Briercrest Seminary in Caronport, Saskatchewan. “It is a reality we all have to face.

The population of Canada is just over 35 million — a little less than the population of California. And yet there are more than 40 theological colleges and seminaries in Canada (counting only those that are accredited or candidates for accreditation in the Association of Theological Schools), compared to 30 in California.

Canada has more theological schools than its population can support, Guretzki believes. And few Canadian theological schools have massive endowments that can provide a cushion when tuition revenue and bursaries (government-financed scholarships) decline.

So, what’s a seminary or theological college to do? For Briercrest, the last few years have allowed them to focus on their purpose. “We are a seminary. We are aiming to equip the church,” Guretzki says. “You can sometimes lose sight of that, and you get caught up in trying to keep afloat, and keep your degrees.”

At Briercrest, the tightening of vision has resulted in even more flexible degree packages to suit students who are professionals coming from other fields. “We’ve really tried to say that education is a means; it’s not an end,” Guretzki says. “It’s a means for equipping and professional development. It’s not getting a degree as the end. That’s subtle, but it really makes a difference in how you think about things.”

Nearly 4,000 kilometers to the east, the Atlantic School of Theology has an inspiring view of the waters of the Northwest Arm of Halifax Harbour. Neale Bennet, the new president, arrived with a realistic view of the Canadian church.

“Something is dying and something is being reborn,” he says. “We need leaders who can work both. What’s being newly born is not apparent to us yet, but what is clear is the challenge to make the gospel relevant in a very different world than the one we have been living in.”

Bennet stresses two words to sum up the kind of leaders needed for the new reality of the Canadian church — pastoral and entrepreneurial. “We need leaders who are pastoral, able to care for dying individuals, congregations, and communities, able to accompany communities and people in letting go of something that is falling away,” he says.

“But we also need entrepreneurial leaders who are collaborative, creative experimenters and are willing to try new things in a compelling way. We need leaders who are able to enter into unusual partnerships.” Bennet believes that more and more of these new leaders will come from students whose sense of vocation is lived out in a secular context.

“In the future, what we want to do with the M.Div. and continuing education is to offer students the ability to learn some really practical, really useful leadership skills around things like leading change, being collaborative, taking risks, being creative, being innovative,” he says. “You can learn these things.”

Stanley E. Porter, president of McMaster Divinity College in Hamilton, Ontario, agrees that “things are changing a lot.” Porter’s school is officially Baptist, but he doesn’t expect the denomination to bolster his student body or prop up his budget. “The amount of students and funding we get from our denomination is going down all the time,” he says, echoing nearly every denominational seminary leader.

What has gone up are students from other denominations attending McMaster. “We’re trying to provide the kind of theological education that will prepare someone to minister in a broadly evangelical setting,” says Porter. And many of his students, from a variety of church traditions, are looking for something other than the master of divinity.

“The M.Div. used to be thought of as the kind of degree to get, but it is declining in attractiveness,” says Porter. “It’s a three-year degree, and with the busyness of life, students are trying to find other ways to suit their purposes.” Porter adds, “We’re asking, ‘What is the appropriate way to educate people for the current situation and the future?’” He notes that McMaster has made changes to the structure of its degrees.

What’s the future of the church in Canada? Porter is thoughtful. “It would be wonderful if we had a revival, and the churches would find themselves full of people wanting to know Christ,” he says. “But I suspect that the church will continue to struggle.”

He adds, “There are all sorts of increasing social and cultural forces at play.” In Canada today, both church and academy continue to wrestle with those forces.