|

| Andrew F. Walls, a veteran missiologist, has taught at universities in Sierra Leone and Nigeria. A Scot by birth, he is the founder of the Centre for Christianity in the Non-Western World at the University of Edinburgh. |

Theology is about making Christian decisions in critical situations; it is in the southern continents that those decisions will be most pressing. Christianity is in recession in Western countries.What happens in Africa, Asia, Latin America, and the Pacific will determine what the Christianity of the twenty-first and twenty-second centuries will be like. If Africa and Asia and Latin America do not develop a proper capacity for leadership in theological studies, there will for practical purposes be no theological studies anywhere worth caring about.

The Western academy is sick. Developed as a product of Christian concern, the earliest universities were church institutions holding as sacred duties the preservation and promotion of learning and imparting it to new generations. Over the centuries they became secular institutions, but they retained the old ideals in secular form. In the European tradition, the state replaced the church in maintaining and renewing them, but by the twentieth century the burden was too great and the corporate world, was called in to make the enterprise viable. The universities thus find themselves the pensioners of global capitalism: the path of most academic merit is that which brings in the most private funding.

Another danger afflicts the Western academy, particularly noticeable in the United States. Professors have become a guild, a profession, and the academy a career. Increasingly that career is becoming analogous to careers in the business world, competitive and individualistic. Originally the university was a fellowship of scholars; it has become an assemblage of workshops where individual scholars work individually.

Research in the humanities, including religion, is dominated by a number of foundations, so professors become adept at seeking out the projects that will please program officers and foundation boards. We need a return to the ideal of scholarship for the glory of God, of the academic life as a liberating search for truth. Perhaps the scholarly vocation will begin anew in the non-Western world and a new breed of scholars arise.

|

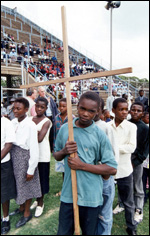

| Young Africans, like these participants in a procession at a 1998 gathering of the World Council of Churches in Harare, Zimbabwe, will give a new shape to twenty-first century Christian thought. |

Agenda for the New Century

The theological enterprise of the twenty-first century will include thinking Christ into the entire cultural framework of Africa and the Asian countries, so that the Lord of All really rules past and present. It is convenient—because the issues there are so stark—to choose some tasks that will belong particularly to Africa to illustrate the larger undertaking. The first of these is rethinking the framework of theology.

Most African theological thinking necessarily started within the particular Western framework that belonged to those who transmitted the Christian message, but neither party was conscious of how far that framework was the product of a particular period of Western cultural history. It is not that the doctrines of Trinity and Incarnation and Atonement and so on are Western ideas; but rather that the framework that holds them together comes out of Western experience. One element is crucial to the way that framework has been constituted in modern times, and African experience has not been symmetrical with it.

The complex series of intellectual movements which we designate collectively as the Enlightenment presented the greatest challenge to the Christianity of the West since the rise of Islam. Its exaltation of reason and of the autonomous individual self battered the supports that had upheld Western Christianity since the barbarian conversion: revelation and the corporate consciousness as expressed in Christendom. Further, the view of the universe became concentrated on the empirical world that we can see and feel.

The Enlightenment turned upside down much of traditional thought. It could have strangled Western Christianity, but instead Christianity set about penetrating Enlightenment thought. The Evangelical Revival made a special contribution to the new synthesis, since it demonstrated that Christianity, formerly expressed essentially corporately within the concept of Christendom, could be reconciled with the individual consciousness and the new primacy of the autonomous self. There remained a stream of Enlightenment thinking that was hostile, or at least unfavorable, to Christianity, and that stream was to broaden in the twentieth century. But a Christianized form of the Enlightenment developed and became the dominant Western expression of Christianity.

The modern missionary movement was deeply influenced by the Enlightenment and its concern with education and health care, its confidence in science and technology, its ideas about civilization as the fruit of evangelization. Generations of missionaries set forth the Enlightenment worldview that had given shape to their theology.

|

| This view of Earth, as seen and photographed by the Apollo 17 astronauts as they hurtled toward the moon in 1972, shows the global south. The coasts of Africa, Saudi Arabia, and the island of Madagascar are easily visible through the clouds. |

Fundamental to that view was a demarcated frontier between the empirical world—the world of what we can see and touch—and the world of spirit. Natural could, and must, be distinguished from supernatural. The non-Christian and anti-Christian wing of the Enlightenment argued that there is nothing on the other side of the frontier of the empirical world, or, if there is, we can know nothing about it. The greater part of the Western secular academy now works on that assumption, even in the study of religion.

The Christian Enlightenment accepted the frontier between the worlds but asserted that there were identifiable crossing places: the Incarnation, the Resurrection, revelations, prayer, perhaps miracles. But the frontier was generally closed, and theological activity was sometimes a matter of deciding where the bona fide crossing points were. So much of the Old Testament could not be accommodated within an Enlightenment universe that Enlightenment Christians developed ways of reading it at a certain distance; and even some features of the New Testament and the apostolic church—prophecy, for instance, healing, and other works of power—were designated as frontier crossings formerly in use but no longer available.

In Africa, Different Visions

In such a framework the gospel came to Africa and was accepted and appropriated by Africans. But African visions of the world were different. The frontier between the empirical world and the spiritual world was being crossed and recrossed every day in both directions. Africans responded to the gospel in multitudes, but they could not easily lose the vision of that open frontier. As a result, the theology they inherited, and the church practice based upon it, frequently did not seem to fit the facts of daily experience.

Western theology is pared down to fit a small-scale universe. Most Africans, even when they were participating in Enlightenment activities, lived in a larger universe where the frontier was still open. The distinction between natural and supernatural was not easy to preserve. In an Enlightenment universe, for instance, witchcraft does not exist: Enlightenment Christianity swept witch and witch doctor together, along with every form of magic and divination and most forms of traditional healing, into a single pile of refuse designated “superstition.”

|

| Members of the Daughters of the Redeemer, a Zambian religious community, celebrate the Vatican’s approval of the formation of their order at a liturgy in July in Mount Zion, a town near Lusaka, the nation’s capital. |

The resultant gap has been incalculably damaging. Multitudes of Christians have not known what to do in emergencies for which traditional Africa had traditional remedies. They live in a larger, more populated world, and they see things that church theology and practice does not envisage. So they go to the diviner, but secretly, and with a bad conscience. It is an act not of apostasy, but of desperation.

The people who first explored the gap between worldview and theology were often semi-educated. They could see that, for Christians, God in Christ ought to fill the whole world and relate to everything in it, but the theological framework they inherited left huge untouched areas. And as they read the New Testament themselves, they saw those stretches of material that Enlightenment-influenced theology had bracketed out. They put two and two together and did some theological reconstruction. There is evidence of creative informal theology all over Africa, carried out by people who did not realize they were theologians. Some were among the founders of the early African-instituted, or “Spiritual,” churches, and the problem they addressed was essentially the gap between theology and worldview. Commonly seen as being on the margins of Christianity, many were at heart radically Christian, seeking to actualize the saving activity of God in Christ in the world as large numbers of Africans saw it.

Much has happened since those early days, Africa is now one of the Christian heartlands. The missionary movement brought the gospel to Africa, and brought the Enlightenment with it. Africans took the gospel and something from the Enlightenment too. But as we look at the continent, with its burgeoning Christian communities, we must conclude that part of the strength of Christianity in Africa today is due to its independence from the Enlightenment.

African Christian practice now recognizes the need for Christ to fill the world as Africans see it, to cope with the open frontier between the empirical and spiritual worlds. Plenty of church practice now takes the universe that most Africans live in seriously and seeks to demonstrate the power and love of Christ within it. But there is also a great deal of confusion and ambiguity, some of which comes from imported aspects of the charismatic movement, the message that prosperity and health are the normal state of the true Christian life. What is the outcome when prosperity does not closely ensue? If I have not received the blessing I should, who is responsible? Suspicion is the very seedbed of witchcraft accusation, and hatred the very essence of witchcraft itself. And so, what brought delighted liberation turns back again to bondage.

Grasping the Nature of Evil

|

| India, seen in the center of this global view, may become “the most testing environment in which the Christian faith has yet had to survive.” |

The context in which the new ministries have arisen has also produced a tendency to deal with the demonic solely in terms of individual pathology. This can mask its presence in the way societies (including the church) are organized, not to speak of the mystery of iniquity. It could inhibit African Christian thinking from grappling with massive irruptions of evil such as genocide. Western Christian theology is still wrestling with the fact of the Holocaust. African theology must not fail to deal with the genocide in Rwanda and, above all, how this happened in our own day in what by most calculations was the most Christian country in Africa. A coherent theology of the open frontier between the empirical and spiritual worlds could develop immeasurably the ecumenical understanding of the nature

of evil.

The African intellectual matrix is also likely to call for a theology of relationships, of belonging. This in turn could lead to a new approach to the doctrine of the state. The classical doctrines of church and state have no place for the various layers of loyalty and identity that Africa knows. The doctrine of the family, too, needs a new framework, for in its Western development no one thought of the ancestors, “the living dead” in John Mbiti’s phrase, as part of the family. There is a need for reconception of the framework of theological thinking to cope with a larger universe and to bring coherence and confidence into areas where preaching and practice have already instinctively begun to move.

In all this, we have spoken only of Africa. The theological vigor needed in the twenty-first century becomes evident when we consider the work that interaction with the cultures of Asia will bring: in India, for instance, perhaps the most testing environment in which the Christian faith has yet had to survive; or the other Christian discourses such as those of China and of that line of Christian communities that stretches from the Himalayas through Southeast Asia, and have appeared only in the last century. There has never been such a call for devout minds with a mastery of Scripture, an awareness of earlier Christian thinking, and a confident apprehension of the cultural traditions and realities of life of the southern continents.

One area of revision will be theological education. Generally speaking, the theological curricula across Africa and Asia have followed Western models. But in church history, for instance, these reflect a careful process of selection that makes the West the special focus of the church’s life. And biblical studies are dominated essentially by the results of a chapter of Western intellectual history and its methods. There are other traditions of needing sacred and classical texts that minds conditioned by Confucian and Buddhist approaches may profitably apply to Scripture. For African theology and church history, the old religions of Africa are the materials that, in converted, unconverted, or partly converted form, lie beneath the beliefs and practices of the Christian church there.

Recipe for Theological Change

It is evident that much of the work can only be done in Africa, Asia, Latin America. If the churches of these continents do not produce theological leadership, the principal theaters of Christian mission in the century now opening will languish in confusion.

|

| African church buildings, like this Methodist church in Ntakira, Zimbabwe, often can barely contain their burgeoning congregations. |

The ingredients required for the theological revolution will include:

- A renewal of the sense of Christian vocation to scholarship, with the anchoring of Christian scholarship in Christian mission. Meeting the demands envisaged here require long training, constant self-discipline, intense labor without being much noticed. Christian scholarship in the new situation is going to require the sort of vocational sense that in one age of the church called people to be monks and, in another, to be missionaries.

- A research climate. The southern continents are packed with amazing resources: historical, biblical, theological, phenomenological. But their institutions are not always aware of the gold mines within their reach. They have the capacity to collect and preserve research materials, to foster a sense of inquiry, to develop forums for discussion and scholarly investigation. The Western university has become an ivory tower, and the economic realities of Africa and south Asia make it clear that the ivory tower is unattainable there. But other traditions of scholarship, particularly one belonging to India, may have particular relevance for Christians. The ashram was, and is, a community of people living a simple life of worship and study together. Some Christian ashrams have already come into being specially for this scholarly purpose in Africa, Asia, and Latin America. But equally the Christian ashram could arise in a preexisting institution (a seminary or a university department, for instance) if it maintained the devout spirit, the active, cooperative fellowship, and the research climate.

- Exacting standards. These are of the nature of scholarship, and can be achieved without grand surroundings.

- Collegial attitudes. The ashram model is of scholarly cooperation, of sharing resources and corporate responsibility.

- Pioneering spirit. The new scholarship needs Origens: innovators who both open up new fields and develop ways of exploring them adequately. And, as Origen’s own career makes clear, such experimental scholarship is risky.

- Dual education. The effectiveness of scholarship will depend on its depths of understanding in the biblical and Christian material and the local society in all its aspects. It will need people with Origen’s dual education, where the Greek interpenetrated with the Christian so that they could be most Christian when most Greek and most Greek when most Christian.

- A catholic attitude to knowledge. Specialization is inevitable in scholarship, but the new situation needs scholars who, while maintaining and developing their own expertise, are willing to listen, learn, and absorb Christian learning from every discipline, sacred and secular.

- A lively interactive sense of world Christianity. Perhaps the largest issue for the church of Christ in the twenty-first century will be ecumenical. Africa, Asia, and Latin America will be the leading theaters of mission and, it is to be hoped, of theological activity. But will each develop along its own local lines through its own local resources, so that in the end there are a welter of local Christianities with no fellow feeling?

It would fit the postmodern fashion to say that each local Christian discourse is valid and sufficient in itself. But the church is Christ’s body, and the picture we are given in the Epistle to the Ephesians of the relation of different cultural presences in the body is neither of uniformity nor of separated diversity but of mutual possession.

We are one body, and the health of the whole is involved. Cooperation, even in the preparation for assumption of leadership in Christian scholarship by Africa, Asia, and Latin America, could have an effect on the process. But it must be genuine cooperation; the age of dependence (and the assumption of Western leadership) is at end. In any case, many Western institutions are not well placed to assist in the development of theological leadership outside the West; they have neither the experience nor the expertise, and there is a sad trail of Ph.D.s across the world whose long years of study in the West have left them no better, and perhaps worse, equipped for their task than before. Perhaps the single most valuable enterprise would be the harnessing of technology to bring about a genuine sharing of library resources. True sharing of academic resources would be a small step toward the enjoyment of the riches that will be available in the body of Christ as his people from all over the world grow up in him. And the discoveries about Christ that are made in the African, Asian, and Latin American heartlands will belong to us all.

This article is excerpted and adopted from a longer piece titled “Christian Scholarship and the Demographic Transformation of the Church” that appeared in Theological Literacy for the Twenty-first Century, edited by Rodney L. Petersen with Nancy M. Rourke (Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing Company, 445 pages, $30 paper, 2002). Reprinted here by permission.